Walid Jumblatt Abdullah, an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Global Affairs at Nanyang Technological University, discusses the politics of the 2020 Singapore Budget.

‘Will this year’s budget be a General Election Budget?’ Janadas Devan, Director of the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), posed this question to Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Heng Swee Keat, in January this year. An ‘election budget’ would mean a budget which softens the ground in an election year, with the provision of goodies such as cash transfers or tax rebates. Predictably, Minister Heng declined to answer directly, instead saying that the budget would focus on what Singapore needs both in the short and long terms.

Yet now that it has been announced, one can say with some level of certainty, that it is likely an election budget. From a political analyst’s point of view, there are three takeaways from the budget and the discussions which ensued.

Election budget

To be sure, this year’s budget was far more indicative of an imminent General Election than the previous one. From the cash handouts to assistance for businesses (such as a corporate income tax rebate), it is clear that the budget is much ‘sweeter’ this time round. About an expected $6 billion dollars has been promised to households over the next five years, which is an extremely generous amount, for instance.

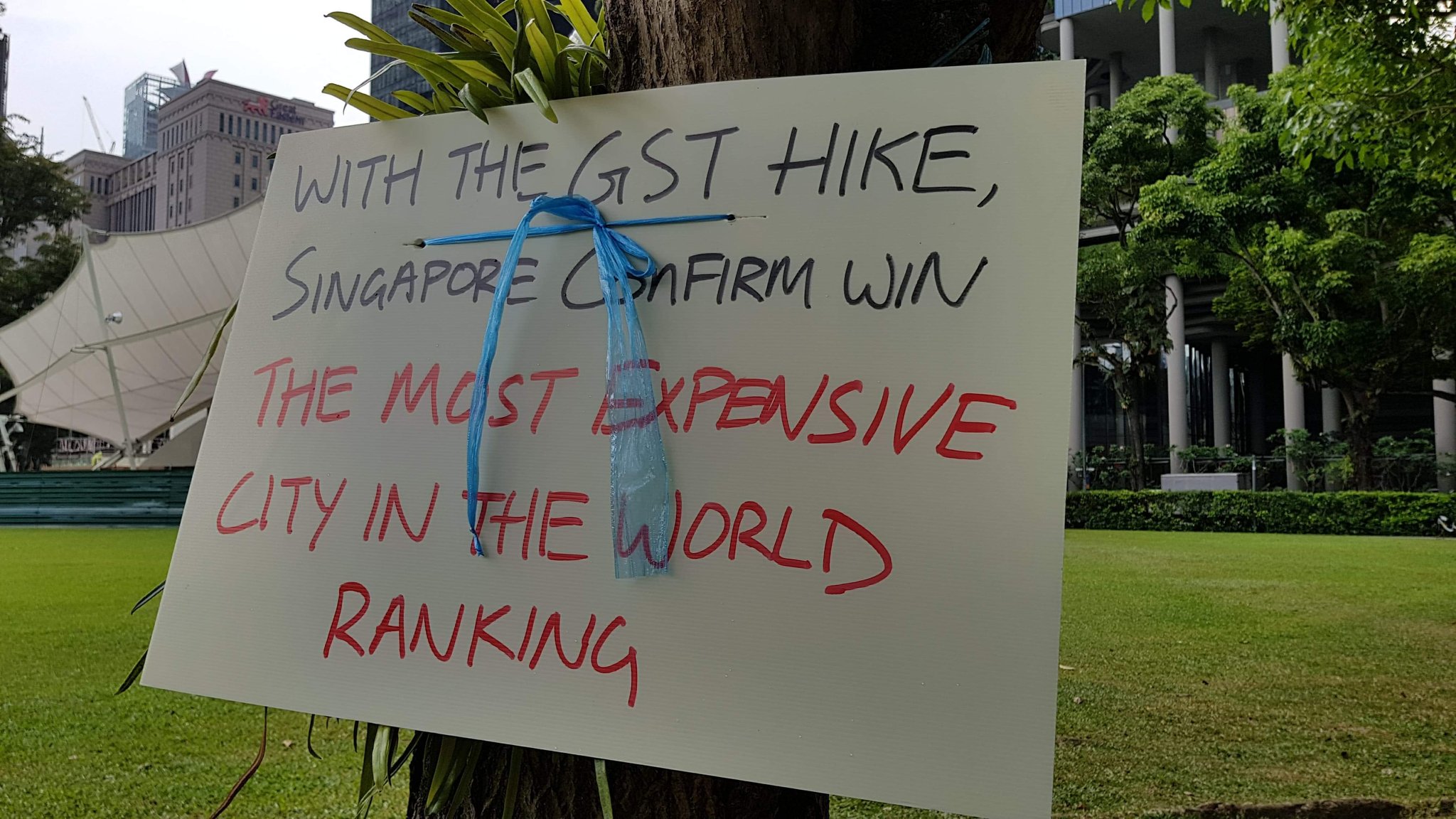

But the most important announcement has to be that the Goods and Services Tax (GST) hike to 9% will not be implemented in 2021. This planned increase was originally announced in 2018, but in response to economic conditions due to the Covid-19 outbreak, its implementation is being delayed. The GST was introduced in 1994 at a rate of 3%, and has been increased progressively to 7%. Notably, the GST rate has never been increased within a year either side of an election, which demonstrates the potentially sticky matter of increasing the cost of living in such a direct manner, even if the government believes such moves may be economically necessary.

It is worth iterating just how pertinent this is. From past experience, elections in Singapore are not likely to turn on issues pertaining to freedoms and individual liberty, such as the Protection against Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) or other legislation. What voters care about the most are still likely material and bread-and-butter matters.

The Malaysian GST was a defining issue of their 2018 General Election, which caused a historical defeat for the then-incumbents. To be sure, the PAP is nowhere near in such danger, but it is true that the time may not be ripe for the introduction of a measure such as the GST hike, with elections looming.

Not that there is anything wrong at all with politicians being concerned about elections. Indeed, politicians caring about elections means that they are concerned with voter sentiments. Politicians do, and should, care about elections, because ultimately, their legitimacy is derived from the people. We should not expect Singapore’s politicians to be different from others in this regard. Somehow, events such as the Budget are not viewed through a political lens. In reality, very few things are ‘apolitical.’

Politics of (possible) recession

In many countries, when the economy is going south, the ruling party loses votes. That trend has not always applied in Singapore. Voters seem to have a flight-to-safety mentality when it comes to the PAP. Perhaps because of its track record in running the country, perhaps because of the lack of a strong opposition, or perhaps because it is the only ruling party Singaporeans have known, the PAP does relatively well in times of economic crises. In 2001, when the economy was shrinking, the PAP attained 75.3% of the vote share.

This apparent bucking of the global trend may also be explained by the observation that, due to Singapore’s open economy, voters are less likely to blame the PAP for downturns, as we seem to be witnessing from the current Covid-19 situation. In fact, one can argue that the PAP leadership has done well in mitigating the crisis. The announcement that Ministers and the President will be taking a one-month pay cut has been symbolically resonant with the electorate; although some have derided the move, stating that it would not affect the Ministers’ standard of living in a significant manner, it still goes some way in leading by example.

Elections are not only about cold, hard facts. Symbolic gestures matter, because humans are not just purely ‘rational’ beings, but are emotional and spiritual creatures as well. This move is likely to generate goodwill amongst many citizens. Is it the most economically sound policy? If corporations follow the lead of the government, resulting in more saving and less spending, then perhaps not, since a recession becomes even more likely when people are more frugal. Lower consumption levels due to fears of a recession, may lead to a self-fulfilling recession. But politically, it makes a lot of sense.

Inequality: the issue of our time

In recent years, inequality has been at the forefront of national discourse, with Singaporeans becoming more cognizant of it. Earlier this year, for instance, PM Lee Hsien Loong said that the government would strengthen social safety nets to help the vulnerable. Just in the past couple of weeks, he also said that “inequality and social mobility are key issues in our time”.

This year’s budget, and the government’s rhetoric over the past couple of years – exemplified by PM’s comments quoted – above have at least in part been affected by the bottom-up discourse engendered on inequality. There has been a palpable reaction to public opinion. This is in no small part due to efforts such as Teo You Yenn’s This is What Inequality Looks Like, which became a national bestseller.

While the government has undoubtedly undertaken more efforts to combat inequality, one can also question the utility of giveaways to the upper and middle-class, which is a common feature of budgets. For people who can afford it, what is really the marginal benefit of 100 or 200 dollars? By comparison, for a lower-income family, that could mean close to a month’s worth of groceries. A government as secure in its power as the PAP should be able to lead public opinion, and not merely follow it. With discussions on inequality coming to the mainstream, and more Singaporeans accepting that inequality is undeniably a scourge of modern society, the public is ripe for more redistributive policies, even in an election year, so perhaps this was an opportunity missed.

For media: Are you interested in republishing this article? Please see our guidelines here.